I grew up in a family that was doctor-averse.

They weren’t anti-vax, anti-science, ideological weirdos. But it was complicated.

Depression-era frugality led to most of my parents’ “I’ve seen worse” responses to childhood lacerations and stomach viruses experienced by me and my three siblings. But my parents’ aversion to paying for medical treatment also was colored by my father’s DVM degree: My father’s license to treat mammals extended to his children. The fact that we all reached maturity is a testament not just to the public health advances that gave us school vaccinations and fluoride in our toothpaste. Surviving to the age of legal voting was due to the gallon jar of veterinary-grade tetracycline on the kitchen counter and the fact that antibiotic resistance hadn’t yet been invented. Childhood accidents received the same DIY treatment. My youngest brother, fading back to catch a football, once sliced open his head on an electrical box. My father mended that gash on our kitchen table, with my brother stoically trading local anesthesia for efficiency.

My family, of hardy pioneer stock, accepted that children living on a farm would bash or slice themselves open with some regularity, and that the gaping wounds would usually heal themselves, perhaps with help from a needle plucked from the autoclave in my dad’s clinic. When I was in high school, I belatedly noticed a gash hidden below my ankle joint, received when a rusty barn door blew open. By the time I paid it any attention, it was making rather a spectacle of itself. I couldn’t get a good look at it, but it must have been unappealing, because my mother drove me to the local osteopath for stitches. For the only time in our lives. Sincere Dr. Fast tried to make sense of the mangled, half-healed tissue presented to him. As he ripped up the scabbed-over bits with a scalpel to put in fresh sutures, Dr. Fast queried my mother, “Has she been away at school?” No, returned my mother mildly. “Has she been on a trip?” Ah, now she saw where this was going. No, she said firmly. “She’s eaten three meals a day at my table.” The entire family has been living with that god-awful, vultures-are-circling, “Snows of Kilimanjaro” piece of weeping flesh for most of a week. Your point?

My family’s cost-effective system worked fabulously, even for me and my unfortunate ankle, until it met a virus rarely discussed by people living in countries with plumbing and air conditioning and credit cards. The Mayo Clinic recommends, “Make sure your own vaccinations are current.” Trust the Minnesota folks on this one, friends, or you’ll be part of your state’s epidemiological statistics, and not in the good way. As evidence, I submit the following tale.

Before I started my sophomore year of college, my cousin Candy took me for an outing to fancy Quail Springs Mall in Edmond, the white-people Oklahoma City suburb. Outings with Candy, the shopping savant, can be exhausting even for those in fighting trim. This time, however, I wasn’t just tired. My throat hurt in a way I didn’t know throats could hurt. Consequently, my requests escalated from, “Can we leave in half an hour?” to “How about we pull into that emergency room in Kingfisher and visit my brother the pharmacist?”

There’s no waiting in line in Kingfisher Memorial Hospital, and you get service from the same doctor who attended your delivery. The very doctor who knows all about the family tetracycline treatments and has warned my parents, “When they start barking, don’t bring them to me.” Dr. McIntyre swabbed my throat, prescribed antibiotics, and pledged to call when the culture came back.

Now begins the part of this anti-doctor story belonging to my mother. She and my father both had a less-is-more approach to health care, but my mother’s relationship to medicine was, well, complicated. Her response to my health predicament started with doctor shaming. My mother was incensed that I had walked into an emergency room, her point being that if you are walking, by definition you are not an emergency. Despite my profligacy, I was a miserable study in infectious diseases until the antibiotics kicked in. Life was fine until the prescription ran out while I was at sorority rush and that sore throat returned. The university was all about avoiding liability, so some responsible adult took me to the campus infirmary. I was functional again.

But where were those lab results? When I drove back to Kingfisher to get the rest of the story, Dr. McIntyre explained why the results had taken longer than expected. He had sent my sample to the state lab for a do-over, because he didn’t believe that I actually had (wait for it) diphtheria. Which I did. Which meant that I got upgraded to diphtheria-level antibiotics. Believe the science. God wants you to take these meds.

Couple of things will be happening pretty quickly about now. I call my cousin Candy to tell her what I’ve exposed her to. She and her mother will be simultaneously horrified (“You slept in the same bed!”) and compassionate (“She must have outgrown her immunization. Or something.”) No one would have presumed that my parents would have raised an unvaccinated child, so no one said out loud the most likely explanation of my condition. It takes five DTaP shots for children to achieve full protection against diphtheria. I probably hadn’t been to the doctor five times in my entire life. Birth order is everything, and parents cut some corners for the fourth child.

When I walked up the steps of my mother’s house with my new prescription, my mother and I were both furious. She was predictably angry because I’d gone to the doctor, again, rather than reasonably take care of myself. This time, my self-righteous teenaged self returned fire with weapons-grade guilt. “Get my rest? Take care of myself?” Here, I’m ashamed that I inserted some versions of “Ha!” or “Oh yeah?” into this exchange. I was 19 years old and insufferable. Then I delivered the punchline: “I’ve got diphtheria!” Cruel as it seems now, I walked on and didn’t wait for her reaction. Because here’s what we both knew: At ages 8 and 9, my mother and her sister Iris contracted diphtheria, and her sister died.

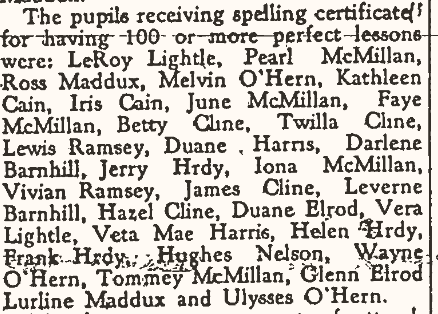

My virus-ridden teen-aged self opened a door to family psychodrama that had been shut since 1929. Other than a single photograph hanging in my grandmother’s front bedroom, Aunt Iris had disappeared into the ether. I never heard my grandmother speak of her. Iris and my mother were Irish twins; she was my mother’s constant companion. Yet my mother was the girl that lived, and she and my grandmother seemed silently to agree that some mistake had been made. Best not to speak of it. In this environment of omerta, it took me ages to discover the origins of the nickname I heard my mother called at my grandmother’s house. As a child, I couldn’t fathom why my mother’s own family couldn’t pronounce her name correctly–”Kathleen.” Instead, they called her the name as Iris pronounced it when my mother was a baby: “Kappy-tu,” shortened to “Kappy.” Each time her parents or four younger brothers said my mother’s name, Iris’s word was in their mouths.

As a bored child, I once sat at the kitchen table doing some summer activity while my mother washed dishes, her back to me, as we chatted about her childhood home. Her father loved her mother so much he built her a new house when none of the other farmers were taking care of their wives so well. Her house had an electric generator in its basement, very fancy. “Did you have a cistern?” I asked. Our farmhouse has one, and I thought every well-appointed home should have such an ingenious rainwater collection system. Oddly, my mother didn’t answer. I thought she didn’t hear me, so I repeated my question. “Did you have a cistern?” Now I turned to look at her unmoving back. She didn’t look at me, and I must have asked again, prompting her to finally say, without turning around, “Yes, but she died when she was very young.” “Oh no, I said cistern, for your water!” But that conversation was over, and would, it appeared, stay closed indefinitely. After I contracted diphtheria, I finished my course of antibiotics with no comparisons made to that earlier, deadlier outbreak in the fancy house with the electric generator.

I had just one other conversation with my mother about diphtheria, but it cast my childhood’s lack of doctors in an entirely different light. During a long layover in the Atlanta airport, I had my mother to myself, with very few distractions. In her own home or mine, she would have been cleaning, folding, cooking. But in that time before cell phones, all we could do was talk. She told me about living on the Army base in New Jersey, and her friends in the Women’s Army Corps. She described the days when my brothers and I were born. And she told me about her sister.

A family in her country neighborhood was sick, so my grandmother carried them food. My mother and her sister stayed at the gate of the family’s yard while her mother delivered the basket to their door. Some time after this visit, the girls became sick. The doctor came to the house and looked down their throats, covered with the leathery patches that diphtheria creates. Patches can grow large enough to restrict breathing, so a doctor would want to remove them. Iris later developed something like pneumonia. When her parents took Iris to the hospital, my mother’s Grandmother O’Hern came to stay with the remaining sick child, telling my mother that doctors would make her sister better. My mother, eight years old, told her grandmother, “No. She’s not coming back.”

When my Uncle Gayle came to my mother’s funeral, I told him the food delivery story. His response was “Jesus Christ.” Gayle seemed to confirm my suspicions about the origin of my mother’s conflict with her own mother. Try as she might, my mother was only ever going to look like an accusation. She was the presence that pointed to her sister’s absence. No one would have been cruel enough to blame my grandmother Nora Cain for the death of her child, but they wouldn’t have needed to: She was already there.

My mother’s most revealing detail in the Atlanta airport arose from stories about her World War II military service at Fort Dix. I got a funny story about a New York City plastic surgeon who offered to reshape her robust Irish nose to her heart’s desire. A free nose! But she declined; it was her father’s nose, too, and she wanted to keep it. In discussing Army health care, she mentioned the vaccinations she got when she arrived. But wait, I interrupted. Didn’t you already have those? Didn’t doctors come to your school to vaccinate students? Yes, they did, my mother agreed. But she waited in the bathroom until the doctors were gone.

If I had taken a bite from my airport Cinnabon, I would have missed this new information. Apparently doctors terrified my mother so much that she hid in bathrooms to avoid them. In this context, my family’s avoidance of medicine wasn’t just about frugality, although, sure, we were cheap. It was about trauma. Doctors scrape little girls’ throats with scalpels to help them breathe. And when they come to your house, your sister dies. Why would you want any of that?

As a child, I thought my parents embraced the same anti-medicine stance. On reflection, I see that my father had a triage system going, sorting out what conditions needed immediate attention and what could wait. My oldest brother got his tonsils removed; my youngest got attention before his appendix burst. My father spent a week in the hospital while various doctors figured out his prostate issues. My mother, however, lost her trust in doctors when she was eight years old, and she never got it back. Consequently, doctors were not her first call when she experienced the onset of a sudden inexplicable, debilitating neck pain. She put herself to bed and stayed there until a family friend finally drove her to a small regional hospital, where rural healthcare failed her a final time. Women’s heart attacks don’t look like men’s heart attacks. So the hospital sent her home, where she died the next day.

During that layover in the Atlanta airport, my mother revealed the fear around which she had organized her life: Doctors can cause us the greatest pain because we encounter them when we are most vulnerable. At the age when my own children were managing strep throat with tasty pink Amoxicillin and popsicle therapy, my mother was facing down the loss of her sister, her survivor’s guilt, and a growing awareness that her own mother’s grief would make her life more complicated. My mother could have adopted any number of self-destructive coping strategies at this point; of the choices available to her, blaming her doctors seems like an absolutely genius solution. My mother never overcame that fear, but she tamped it down hard. And she compensated for her fear with a courageous, demanding ferocity that looked like love. Because it was.

This is such a powerful piece. The confounding tragedy of your mom’s heart attack still enrages me to think about, and you’ve really unwound so many layers of her puzzle–and yours. (Also. I feel like I’ve seen the photo of the Cain sisters, c.1928, before. Is that not true? I thought maybe I’d see it here.)

LikeLike